Discover How Various Cultures Calculate and Celebrate Age Differently

Age is one of the most fundamental aspects of human identity, yet the way we calculate and celebrate it varies significantly across cultures. While most Western societies follow a straightforward system based on the number of birthdays since birth, other cultures have developed unique methods that reflect their philosophical, social, and cultural values. Understanding these differences offers fascinating insights into how societies conceptualize time, life stages, and human development.

The Western Age System: Counting from Zero

In Western cultures, including most of Europe, the Americas, and other regions influenced by Western traditions, age calculation is relatively straightforward. A person is considered zero years old at birth and gains one year of age on each subsequent birthday. This system, known as the “international age” or “calendar age,” is based purely on the passage of time since the moment of birth.

For example, a baby born on January 1, 2020, would be considered one year old on January 1, 2021, two years old on January 1, 2022, and so forth. This method is linear, precise, and tied to the Gregorian calendar used in most of the modern world.

The Western approach to age reflects individualism and precision, treating age as a personal metric that marks the exact duration of one’s existence. Birthdays are celebrated as personal milestones, often with parties, gifts, and special recognition of the individual.

Quick Comparison: How a Baby Born on December 31, 2024, Would Age

To illustrate the dramatic differences between systems, consider this example:

| Date | Western Age | Traditional Korean Age | Chinese Nominal Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 31, 2024 (Birth) | 0 years | 1 year | 1 year |

| January 1, 2025 | 0 years (1 day old) | 2 years | 2 years |

| December 31, 2025 | 1 year | 2 years | 2 years |

| January 1, 2026 | 1 year (1 day past birthday) | 3 years | 3 years |

As shown, the same child could be referred to as “one year old,” “two years old,” or “three years old” depending on the cultural context—all at the same moment in time!

The East Asian Counting System: Born at One

In contrast, traditional East Asian cultures—particularly in Korea, China, and Vietnam—have historically used a different age-counting system that can make someone appear one or even two years older than their Western age.

Korean Age System (Sesijojeop)

The traditional Korean age system operates on two key principles:

- Everyone is one year old at birth: Koreans traditionally believe that the time spent in the womb counts as the first year of life, so a baby is considered one year old from the moment of birth.

- Everyone ages together on New Year’s Day: Rather than aging on individual birthdays, all Koreans add a year to their age on the first day of the lunar new year (Seollal). This means a baby born on December 31st would turn two years old just one day later on January 1st.

This system creates a strong sense of collective experience and generational identity. It emphasizes the communal nature of aging and the importance of one’s year cohort rather than individual birth dates.

Real-World Example: Consider someone born on December 31, 2023. By Western calculation, they would be one year old on December 31, 2024. However, under the traditional Korean system, they would be:

- One year old at birth (December 31, 2023)

- Two years old the very next day (January 1, 2024)

- Three years old on January 1, 2025

This means when they are only 365 days old by Western calculation, they are already considered three years old in traditional Korean age.

Social Impact: This difference affects daily life significantly. In Korea, knowing someone’s birth year is often more important than their exact birthday. People born in the same year form a “dong-gap” (same age) group, and this bond influences everything from military service cohorts to school year placement to workplace hierarchies. The terms “oppa” (older brother, used by females), “hyung” (older brother, used by males), “unnie” (older sister, used by females), and “noona” (older sister, used by males) are used based on this age hierarchy, even for people born just months apart.

However, in June 2023, South Korea officially adopted the international age system for legal and administrative purposes, though many Koreans still use the traditional system in informal settings. This change was made to reduce confusion in medical care, legal contracts, and international dealings.

Chinese Traditional System

Traditional Chinese age calculation follows a similar principle to the Korean system, where a person is one year old at birth. However, the specific implementation has varied throughout different dynasties and regions:

- Nominal Age (虚岁, xūsuì): This traditional system counts the fetus’s time in the womb as the first year of life. Age increases at the Lunar New Year rather than on one’s birthday.

- Full Age (周岁, zhōusuì): Modern China primarily uses this system, which is equivalent to the Western age calculation, counting from zero at birth and increasing on each birthday.

The nominal age system reflects Confucian values of respect for life from conception and the cyclical nature of time marked by lunar calendars. Today, mainland China officially uses the full age system for legal purposes, while the nominal age occasionally appears in traditional contexts or rural areas.

Practical Example: Imagine a baby born on February 5, 2024 (just before Chinese New Year on February 10, 2024):

- At birth: 1 year old (nominal age)

- On February 10, 2024 (Chinese New Year): 2 years old (nominal age)

- By February 5, 2025 (first birthday): Still 2 years old by nominal age, but 1 year old by full age

- On February 10, 2025 (next Chinese New Year): 3 years old (nominal age), but still only 1 year old by full age

This creates significant discrepancies, especially for babies born late in the lunar year.

Cultural Context: In traditional Chinese culture, certain ages are considered particularly auspicious or significant. For instance:

- 60 years old (one complete zodiac cycle): Celebrated with a major birthday party

- 70, 80, 90 years: Milestone birthdays celebrated with grand family gatherings

- “Ben Ming Nian” (本命年): Your zodiac year, occurring every 12 years, when you’re supposed to wear red for good luck

Other Cultural Variations

Vietnamese Age System

Vietnam historically followed a system similar to the Korean and Chinese nominal age calculations, where individuals are one year old at birth and gain a year at Tết (Vietnamese New Year). However, modern Vietnam has largely transitioned to the Western system for official purposes.

Specific Example: A Vietnamese baby born on February 10, 2024 (just before Tết, which fell on February 10 that year) would be considered one year old at birth. Just hours or days later at Tết, the baby would become two years old in the traditional system, despite being only days old by Western calculation.

Japanese Age System

Japan once used a similar East Asian counting system called “kazoedoshi” (数え年), where everyone was one year old at birth and aged on New Year’s Day. However, Japan officially abandoned this system in 1950 and now exclusively uses the Western age calculation method.

Historical Context: Before 1950, Japanese people would conduct important ceremonies like the Shichi-Go-San (Seven-Five-Three) festival for children at ages 3, 5, and 7 according to kazoedoshi. This meant some children celebrated these milestones at what Westerners would consider ages 2, 4, and 6.

Ethiopian Calendar System

Ethiopia uses a unique calendar that is approximately seven to eight years behind the Gregorian calendar. This means Ethiopians calculate their age based on a different calendar system entirely, making someone born in 2000 according to the Gregorian calendar only about 16-17 years old in the Ethiopian calendar.

Practical Example: In September 2024 (Gregorian calendar), Ethiopia celebrated the year 2017. An Ethiopian who is 25 years old by their own calendar would be approximately 32-33 years old by Western calculation. This creates interesting situations when Ethiopians travel abroad or interact with international documentation.

Thai Buddhist Calendar

Thailand uses the Buddhist calendar for religious and some official purposes, which is 543 years ahead of the Gregorian calendar. While Thais typically use Western age calculation, important life events are often recorded using the Buddhist Era (BE).

Example: Someone born in 1990 CE would have their birth year recorded as 2533 BE in official Thai documents. When celebrating significant Buddhist ceremonies or astrological readings, the BE year is emphasized over the specific age.

Hindu Coming-of-Age Traditions

In Hindu culture, age milestones are marked by specific samskaras (sacraments). The timing of these ceremonies varies by region and tradition, but they mark important transitions based on both age and astrological considerations.

Specific Ceremonies:

- Annaprashana (first solid food): Typically at 6 months

- Upanayana (sacred thread ceremony): Traditionally between ages 8-12 for boys, marking the beginning of formal education

- Ritu Kala Samskara: Coming-of-age ceremony for girls, often occurring after first menstruation

These ceremonies aren’t strictly age-based but combine biological development, astrological timing, and family tradition.

Jewish Bar and Bat Mitzvah

In Jewish tradition, children reach religious maturity at specific ages calculated from birth: 13 years for boys (Bar Mitzvah) and 12 or 13 years for girls (Bat Mitzvah, depending on tradition).

Cultural Significance: The timing is precise—the ceremony occurs on or after the 13th birthday for boys. From this moment, they are considered adults for religious purposes, responsible for their own actions and able to participate fully in religious life. This represents one of the most clearly defined age-based transitions in any culture.

Maori Coming-of-Age Traditions

Among the Maori people of New Zealand, traditional coming-of-age isn’t marked by a specific numerical age but by the acquisition of cultural knowledge and skills. However, modern Maori often blend traditional markers with contemporary age milestones.

Example: Traditionally, young Maori would undergo various rites of passage when they demonstrated readiness—learning whakapapa (genealogy), mastering traditional arts, or understanding tribal protocols—rather than at a fixed age.

Cultural Significance and Social Implications

The way cultures calculate age extends far beyond simple arithmetic—it reflects deeper values and shapes social interactions:

Hierarchy and Respect: In East Asian societies, age determines social hierarchy and the appropriate level of respect and language used in interactions. Even a few months’ difference in birth can establish who is the “senior” in a relationship, affecting everything from workplace dynamics to friendships.

Specific Workplace Example: In a Korean company, two employees might both be in their late twenties by Western calculation, but if one was born in 1995 and the other in 1996, the 1995-born employee is considered the senior (선배, seonbae) and the other the junior (후배, hubae). The junior would use respectful language forms, pour drinks for the senior, and typically defer to their opinions in group settings. This hierarchy persists regardless of job performance or position, unless there’s a significant rank difference.

Language and Address:

- In Korean, there are seven different levels of formality in speech, partly determined by age relationships

- In Japanese, the sempai-kohai (senior-junior) system affects word choice, verb endings, and even body language

- In Mandarin Chinese, family terms like “ayi” (aunt) or “shushu” (uncle) are used for older strangers as signs of respect

Generational Identity: Systems that have everyone age together on New Year’s create strong cohort identities. In Korea, for instance, people born in the same year form a distinct “age class” and often use special terms to refer to their relationships with those born in preceding or following years.

School Cohort Example: In South Korea, all children born between January 1 and December 31 of the same year start school together, regardless of their actual developmental differences. This creates lifelong bonds among classmates and a strong sense of “our generation” (우리 세대). Famous Korean celebrities often refer to each other as “동갑” (dong-gap, same age) and maintain close friendships primarily with others born in their year.

Coming of Age Traditions: Different age calculation systems influence when certain legal rights and social responsibilities begin. Western cultures typically mark legal adulthood at 18 or 21, while other cultures may emphasize different ages based on their counting systems.

Specific Age Milestones Across Cultures:

- United States: 16 (driving), 18 (voting, military service), 21 (alcohol consumption)

- Japan: 20 (Seijin no Hi – Coming of Age Day ceremony)

- Korea: 19 (international age) for legal adulthood, but social adulthood often recognized earlier

- Mexico: 15 for girls (Quinceañera celebration)

- Brazil: 15 for girls (Festa de Debutantes), though 18 is legal adulthood

- Some Indigenous Australian cultures: Initiation ceremonies at puberty rather than fixed ages

Marriage and Dating Implications: In many Asian cultures, age compatibility in relationships is carefully considered. It’s common for women to prefer dating men who are slightly older (often 1-3 years by Korean age), and certain age gaps are considered more or less acceptable based on traditional zodiac compatibility.

Example: A 28-year-old Korean woman (by international age) might face family pressure to marry soon, as 30 is considered a significant milestone. However, by Korean age, she might already be 29 or 30, intensifying this pressure. Conversely, knowing someone is a “dog year” (1994, 2006, 2018) or “pig year” (1995, 2007, 2019) person can influence perceptions of compatibility before even meeting them.

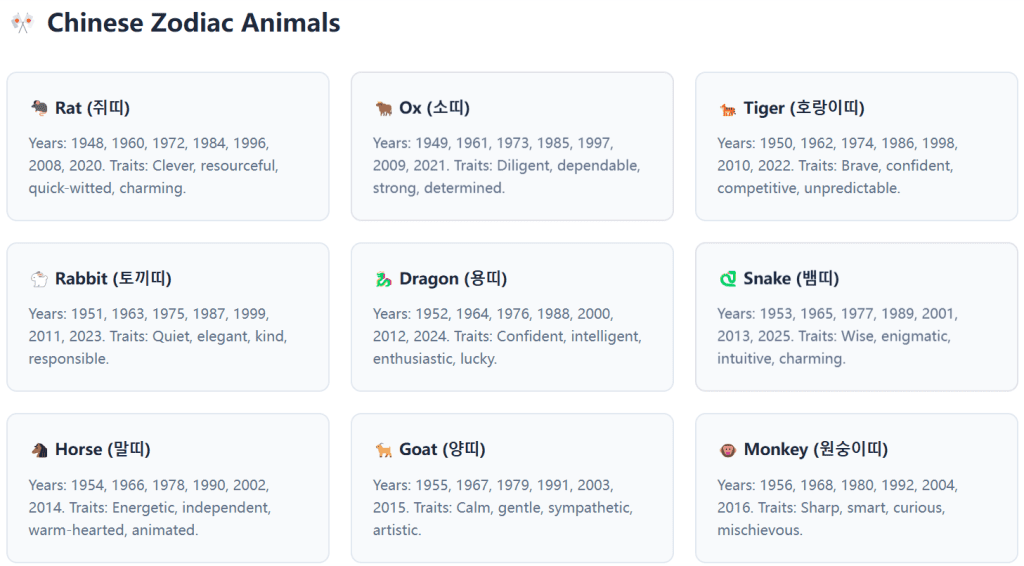

Astrological and Zodiac Considerations: In many Asian cultures, the year of birth in the Chinese zodiac cycle carries significant meaning, often more so than the specific date. This is directly tied to the lunar calendar-based age systems.

Zodiac Year Superstitions:

- Horse Year (马年) women in Chinese culture were traditionally considered undesirable marriage partners, leading to measurably lower birth rates in horse years

- Dragon Year (龙年) babies are highly desired, causing spikes in birth rates during these years (most recently 2012, 2024)

- People in their “Ben Ming Nian” (zodiac year) are advised to be cautious, avoid major decisions, and wear red underwear for protection

- Zodiac compatibility is often consulted before marriages, with certain animal combinations considered more harmonious

Medical and Developmental Contexts: These different age systems can create confusion in medical settings, particularly for pediatric care where precise age is crucial for developmental milestones, vaccinations, and dosing.

Hospital Example: A Korean family visiting a U.S. hospital might tell the doctor their child is “three years old” (Korean age) when the child is actually only 18 months old by international calculation. This could lead to incorrect dosing, inappropriate developmental assessments, or confusion about vaccination schedules. This is one major reason South Korea adopted international age for official purposes in 2023.

Cross-Cultural Age Confusion: Real-World Scenarios

Understanding these different systems becomes particularly important in our globalized world. Here are specific scenarios that illustrate potential confusion:

International Business Meeting: A 25-year-old American businesswoman meets a Korean colleague who says he’s 27. In reality, he might only be 25 or 26 by international age, making them peers rather than him being significantly older. If she treats the interaction as between equals while he expects the deference shown to someone older, it could create subtle tension.

Online Dating Across Borders: A Chinese woman lists her age as 28 on an international dating app, using her nominal age (虚岁). Western matches expect her to be 28 by international calculation, but she might actually be only 26 or 27, creating an awkward situation when they realize the discrepancy.

International Education: A Korean student applying to American universities at “age 18” by Korean calculation might actually be only 16-17 by international age. This affects eligibility for certain programs, scholarships requiring specific ages, and expectations about maturity and independence.

Sports and Competitions: International sports organizations typically use birth year or international age for categorizing youth competitions. An athlete who is “14” by Korean age might actually be young enough to compete in the “under-12” category by international standards, or vice versa.

Legal Age for Travel: A teenager who is “18” by Korean age (therefore legally adult in Korea) might only be 16-17 by international age, causing issues with international travel, hotel bookings, or car rentals that require “18 or older” by the destination country’s calculation.

Retirement and Pension Benefits: A person who worked internationally might calculate when to retire differently depending on which system they use. Someone expecting to retire at “60” by Chinese nominal age might actually be only 58-59 by international standards, potentially affecting pension eligibility in countries using Western age calculation.

Celebrity Age Confusion: International K-pop fans often discover their favorite idol is younger than announced. A star who debuted at “15” by Korean age was likely only 13-14 internationally—still very young, but the difference affects perceptions of their achievements and the appropriateness of certain content.

Modern Trends and Standardization

In our increasingly globalized world, age calculation systems are becoming more standardized:

- Legal Standardization: Many countries with traditional age systems have adopted the Western system for legal, medical, and official documents to facilitate international communication and reduce confusion.

- Dual Systems: Some individuals in East Asian cultures maintain two ages—an international age for official purposes and a traditional age for cultural contexts.

- Generational Shift: Younger generations in countries like Korea and China are increasingly comfortable with the international age system, especially in urban areas and when interacting internationally.

- Digital Age Complications: Online platforms and global services typically use the Western age system, further accelerating the adoption of international age standards.

The diversity in age calculation systems around the world reminds us that even seemingly universal concepts like age are culturally constructed. Whether counting from zero or one, aging individually or collectively, these systems embody different philosophical perspectives on life, time, and human development.

While globalization trends toward standardization, understanding these cultural differences remains important for cross-cultural communication and appreciation. It challenges us to recognize that our own cultural assumptions about age—and by extension, time, maturity, and life stages—are just one of many valid perspectives.

As we navigate an increasingly interconnected world, these differences in age calculation serve as a gentle reminder that the ways we measure and mark the passage of time are as diverse as humanity itself. Whether you’re celebrating a birthday with candles or marking another Lunar New Year, the essence remains the same: acknowledging the journey of life and the experiences that shape who we become.